We are an award winning product design consultancy, we design connected products and instruments for pioneering technology companies.

How IT/OT convergence is redefining robotics design

Reading time 12 mins

Key Points

- IT/OT convergence has shifted robotics design from building isolated machines to designing connected systems that must scale, adapt, and integrate over time.

- Many robotics failures stem not from hardware or software limitations, but from treating system integration as a downstream problem rather than a design constraint.

- Strategic choices around edge computing, cybersecurity, and legacy integration now determine operational resilience and long-term return on investment.

- Organisations that design robots as cyber-physical systems can move risk upstream, enabling faster deployment, safer operation, and continuous improvement. Key takeaway: Early systems thinking in robotics design enables scalable, resilient deployments and reduces costly fixes later.

Ready to design robotics for scale? Avoid costly retrofits—consult an expert now for tailored, system-level guidance.

Ben Mazur

Managing Director

I hope you enjoy reading this post.

If you would like us to develop your next product for you, click here

2025 will arguably be remembered as a turning point in robotics design. From bipedal robots learning to walk within 48 hours of assembly, to medical microbots navigating the bloodstream, and speech-to-reality systems capable of generating functional objects in minutes, robotics has crossed a threshold where rapid learning, adaptability, and autonomy are no longer theoretical. Beneath these visible breakthroughs lies a deeper change shaping the field.

What’s less visible, but far more consequential, is why these advances are happening now—and why they are emerging as part of a broader shift in how robots are designed, connected, and integrated. This shift is being enabled by the maturity of Generative AI and Edge Computing technologies, creating a new bridge between components previously developed in isolation.

The systems thinking shift: From isolated machines to connected nodes

Historically, robots were engineered as self-contained systems. The control software was tightly coupled to the hardware, data remained local, and improvements were made through manual tuning or periodic upgrades. This worked for stable environments like assembly lines or agricultural farms, where precision and reliability were the only metrics that mattered.

Today, expectations and demand are different. Robots are increasingly deployed as nodes in a broader digital ecosystem. They must interact with digital twins, share telemetry with analytics platforms, and integrate into enterprise systems. This requires a design that reconciles two traditionally conflicting domains:

- OT (Operational Technology): Controls physical machines and processes, and is focused on determinism (ensuring the robot moves with microsecond precision and absolute safety).

- IT (Information Technology): Manages data, analytics, and digital systems, focusing on throughput and visibility (moving large volumes of data to the cloud for optimisation).

Designing for convergence means solving the tension between these two. A robot that generates massive data (IT) cannot be allowed to suffer the latency jitters that will compromise its physical stability (OT).

IT/OT convergence is therefore not an add-on or a technology trend layered onto existing designs. Instead, it’s a structural change that defines what robots can do, how they adapt to change, and how much long-term value they can deliver. For organisations investing in robotics, the key takeaway is that understanding this foundational shift is critical—early design choices have a lasting impact on operational flexibility, scalability, and product viability.

IT/OT convergence as a design constraint, not an integration task

For many organisations, integration is still treated as a downstream problem: Robots are designed or purchased to perform a specific task first, with broader system integration only becoming a priority once those robots need to scale, adapt, or deliver insight beyond their immediate function.

For example, a retailer deploys autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) in its distribution centre to reduce picking times and alleviate staff shortages. The robots perform well in isolation, moving goods efficiently and safely across the warehouse floor. Six months later, the business wants to optimise fulfilment based on real-time order priority, staffing levels, and inventory availability across multiple sites. At this point, the limitation becomes clear: while the robots function as machines, they were not designed to operate within a wider digital system. Integrating them with warehouse management, planning, and analytics tools now requires costly custom work — not because the robots failed, but because system integration was treated as a downstream problem rather than a design requirement.

This means robotics design can no longer assume isolation and siloed teams. Robots are now expected to share information, respond to external signals, and operate within a wider operational picture. Whether a robot can later be scaled across sites, optimised remotely, or adapted to new use cases depends largely on how these assumptions were handled at the design stage.

In this new era, designers must treat interoperability as a design constraint, using standards such as ROS 2 (for robotic coordination) or OPC UA (for industrial system integration) from day one. These protocols provide the structured interfaces that allow operational technology, such as motor controllers and sensors, to exchange data reliably with higher-level IT systems, from fleet management software to cloud-based analytics. Crucially, this enables connectivity and intelligence without abandoning the security, segregation, and control principles that traditionally governed air-gapped industrial systems.

Robotics system architecture in a connected environment

As robots become part of connected systems, design must balance two often competing needs: maintaining reliable, predictable operation while enabling transparency and insight beyond the machine itself. In practical terms, this means designers must decide:

- What information the robot exposes and to whom

- How much autonomy it has versus how much it is guided by external systems

- Which decisions remain local and which can be influenced centrally

These are architectural decisions, not technical footnotes. Poorly thought-through designs can lead to robots that technically function but are difficult to integrate, monitor, or adapt. Well-designed systems, by contrast, allow organisations to improve performance, diagnose issues, and evolve operations without redesigning the robot itself.

For business leaders, this is where robotics design starts to influence long-term return on investment. Flexibility and visibility are not features that can easily be added later.

Strategic robot design choices: Edge computing, cybersecurity, and legacy systems

Edge computing as a design decision, not a performance tweak

Edge computing is often framed as a way to reduce latency or improve performance. In converged robotics systems, it plays a far more strategic role: it determines where intelligence lives and how the system behaves under pressure.

Rather than forcing all decisions to occur either entirely on the robot or entirely in the cloud, edge computing distributes intelligence. Certain decisions happen close to operations, while higher-level optimisation and learning take place across connected systems. From a design perspective, this raises fundamental questions:

- What must the robot be able to do independently to remain safe and functional?

- What capabilities depend on network connectivity or shared intelligence?

- How should the system behave when data streams are delayed, degraded, or unavailable?

The answers shape operational risk, resilience, and long-term maintenance costs. Again, these are design-time and systems thinking decisions with lasting consequences, not implementation details to be solved later.

The cybersecurity paradox of connected robotics

As robotics systems converge with enterprise IT, they lose the physical isolation, or the so-called ‘air gap’, that once protected factory floors and operational environments.

This creates a paradox. Connectivity enables remote updates, fleet-level optimisation, and continuous improvement. At the same time, it exposes physical machines to digital threats that can have real-world consequences.

As a result, robotics design must now assume a zero-trust mindset by default. If a robot can receive software updates or instructions over a network, its control systems must be designed to verify, authenticate, and constrain every interaction. Cybersecurity is no longer just about data protection; it is about preventing digital access from becoming a physical risk.

Crucially, this is a design concern too. Retrofitting security after deployment is significantly harder and more expensive than embedding it into system architecture from the outset.

Designing for the ‘brownfield’ reality

Most robots are not deployed into clean, modern environments. They are introduced into brownfield settings: warehouses, factories, and infrastructure sites filled with decades-old equipment, proprietary protocols, legacy systems, and rigid operational constraints.

Modern robotics design must account for this reality. Rather than assuming full system replacement, designers increasingly rely on translation layers or wrappers that allow new autonomous systems to communicate with legacy, PLC-controlled machinery.

This approach acknowledges an uncomfortable truth: innovation rarely arrives all at once. Systems that can coexist, adapt, and integrate with what already exists are far more likely to scale in the real world than those that assume a blank slate.

Cyber-physical systems: Designing for behaviour, not just function

Modern robotics design increasingly treats robots as cyber-physical systems. That is, systems where physical capabilities and digital models are tightly interlinked and aligned. Instead of asking only whether a robot can perform a task (i.e., design for X-function), designers must consider how it responds to variation, how it learns from experience, and how its performance is assessed over time (i.e., design for X-behaviour).

Designing cyber-physical systems requires alignment between:

- The physical capabilities of the robot

- The data it generates and consumes

- The digital models (digital twins) used to analyse or predict its behaviour

For decision-makers, the relevance is straightforward: robots designed this way can be improved without constant physical intervention. Performance optimisation moves upstream into software and data, reducing disruption and increasing adaptability.

Pressure-testing the systems-thinking shift: A real-world robotics design example

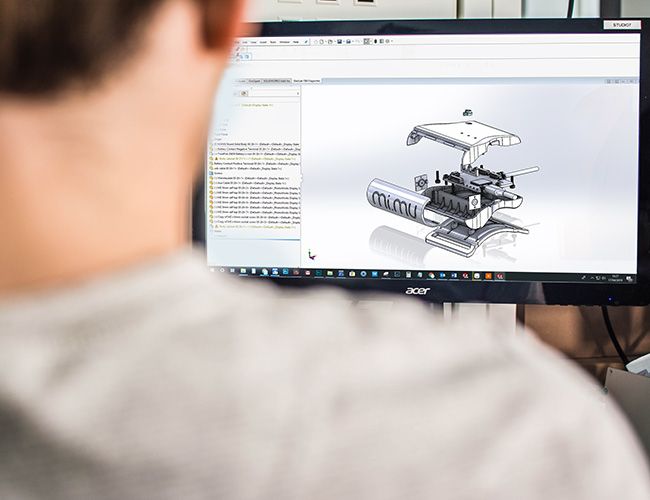

The impact of IT/OT convergence is not theoretical. It is clear in modern industrial robotics environments, such as automotive manufacturing, where robot cells are now designed alongside digital simulation and analytics platforms.

In these cases, robotics systems are no longer validated solely through physical trials. Instead, digital models are used to test behaviour, optimise workflows, and anticipate issues before installation. When deployed, robots operate within a connected framework that continuously feeds operational data back into those models.

The results reported in such environments include:

- Faster commissioning and reduced manual tuning

- More predictable performance once operational

- Improved ability to adapt processes without re-engineering hardware

The significance here is not just efficiency gains. It is the relocation of risk and uncertainty from late-stage deployment to early-stage design — exactly where they are cheapest and easiest to address.

Final Thoughts

The convergence of IT and OT has quietly but fundamentally redefined robotics design. What was once a focus on isolated performance is now a broader consideration of how robots fit into connected, complex, and evolving systems.

For business leaders and decision-makers, the key takeaway is not technical – it’s strategic. Robotics design choices made early on increasingly determine how systems scale and adapt, how they improve, and how much long-term value and resilience they deliver. Those who recognise this shift are better positioned to deploy robotics at scale without accumulating technical or operational debt.

In this context, IT/OT convergence is not a future aspiration. It is the structural reality shaping what modern robotics can, and cannot, become.

At Ignitec, we work with organisations navigating these kinds of system-level design decisions — where robotics, software, and operations intersect. If you’re thinking about how robotics fits into a wider product or platform strategy, it’s a conversation worth having early. Schedule a discovery call with an expert on our team and let’s chat.

The role of prototyping in shaping UK space robotics growth

How can agricultural robotics solutions become more accessible to farmers

Case Study: Autonomous Robotics

FAQ’s

What is robotics design?

Robotics design is the process of defining how a robot’s physical structure, control systems, data flows, and software architecture work together. It goes beyond making a robot perform a task and considers how it behaves, adapts, and integrates within a wider system. Modern robotics design increasingly accounts for connectivity, scalability, and long-term operation.

Why is robotics design no longer just about hardware?

Robots now operate as part of connected digital systems rather than in isolation. Data, software updates, analytics, and integration with other systems influence how robots perform over time. As a result, design decisions must consider both physical and digital behaviour.

How has IT/OT convergence changed robotics design?

IT/OT convergence has connected robots to enterprise data systems while they still perform precise physical tasks. This forces designers to balance real-time control with data sharing and analytics. Robotics design now determines how well a robot can operate safely while remaining connected and adaptable.

Why does robotics design affect scalability?

Early design choices determine whether robots can be deployed across multiple sites or adapted to new use cases. Systems designed in isolation often require costly custom integration later. Scalable robotics design assumes connectivity, interoperability, and change from the outset.

What is the difference between robotics design and robotics engineering?

Robotics engineering focuses on designing and implementing components across mechanics, electronics, and software. Robotics design sets the system-level intent, defining how those components interact and evolve. In practice, design decisions strongly shape engineering outcomes.

How does robotics design influence long-term value?

Robots designed with integration and data flow in mind can be improved through software and analytics rather than physical rework. This reduces disruption and extends useful life. Poor design often locks organisations into inflexible systems, leading to rising maintenance costs.

Why is interoperability important in robotics design?

Interoperability allows robots to communicate reliably with other machines, software platforms, and enterprise systems. Without it, integration becomes complex and expensive. Designing for interoperability enables robots to operate within a wider operational picture.

What role does edge computing play in robotics design?

Edge computing determines where decisions are made within a robotic system. Some intelligence must remain local for safety and reliability, while other functions benefit from shared or cloud-based processing. These choices directly affect resilience and performance.

How does robotics design affect operational risk?

Design determines how a robot behaves when networks fail, data is delayed, or conditions change. Systems that rely too heavily on connectivity can become brittle. Well-designed robots continue operating safely even under degraded conditions.

Why is cybersecurity now part of robotics design?

Connected robots are exposed to digital threats that can have physical consequences. Cybersecurity must therefore be embedded into the control and communication architecture. Treating it as a later add-on increases risk and cost.

What is meant by designing robots as cyber-physical systems?

It means treating physical behaviour and digital models as tightly linked. Robots generate data that feeds analysis, prediction, and optimisation. Design focuses on behaviour over time, not just immediate function.

How does robotics design support continuous improvement?

When robots are designed to share data and integrate with analytics systems, performance can be refined through software updates. This reduces the need for physical changes. Design choices decide whether improvement is easy or disruptive.

Why do many robotics projects struggle after deployment?

Often, because integration and adaptability were not considered during design. Robots may work well individually but fail to fit into wider systems. This creates technical and operational debt over time.

What is brownfield deployment in robotics design?

Brownfield deployment refers to introducing robots into environments with existing legacy equipment and systems. Design must account for older hardware and proprietary protocols. Ignoring this reality limits adoption and scale.

How does robotics design influence return on investment?

Design determines how easily robots can be reused, redeployed, or optimised. Flexible systems deliver value over the long term. Rigid designs often require replacement rather than improvement.

Why is systems thinking important in robotics design?

Robots no longer operate as standalone machines. They interact with people, software, and infrastructure. Systems thinking helps designers anticipate these interactions and avoid hidden constraints.

What decisions must be made early in robotics design?

Key decisions include data ownership, autonomy levels, integration points, and failure behaviour. These are difficult to change later. Early clarity prevents costly redesigns.

How does robotics design affect integration with digital twins?

Design defines what data a robot generates and how accurately it reflects real-world behaviour. This data feeds digital models used for simulation and optimisation. Poor design limits the usefulness of digital twins.

Why does robotics design matter for non-technical decision-makers?

Because early design choices shape cost, risk, and flexibility long after deployment. These outcomes affect strategy, not just engineering. Understanding design implications supports better investment decisions.

When should organisations think about robotics design constraints?

At the very start of exploration or procurement. Waiting until deployment exposes hidden limitations. Early consideration allows robotics to scale without unnecessary complexity.

Get a quote now

Ready to discuss your challenge and find out how we can help? Our rapid, all-in-one solution is here to help with all of your electronic design, software and mechanical design challenges. Get in touch with us now for a free quotation.

Comments

Get the print version

Download a PDF version of our article for easier offline reading and sharing with coworkers.

0 Comments